The poet, songwriter, or artist has a unique relationship with the muse. Painters are inspired by their models, poets dedicate their finest work to their muse, and troubadours express their yearning for the Beloved in song.

I’ve written many songs under the influence of muses— exploring the ways they suddenly appear and utterly change our lives, then just as quickly vanish and break the heart.

Many people, even people who never think of themselves as artists or poets, have met and been inspired by a muse. The muse can come into the life of anyone who is attuned to their presence, anyone who is aware, compassionate, empathetic, and in pursuit of understanding and knowledge. I call this the “poet’s soul.”

You have a poet’s soul…

- if you look for the truth behind reality.

- if you are never satisfied with easy explanations.

- if you recognize that your path is yours to walk alone.

- if you notice things that others do not.

- if you look for the meaning of dreams.

- if you seek the real meaning behind words.

You have a poet’s soul if you fall deeply in love… so deep that you need to find new ways to express it.

So much of what we do as creatives and artists—whether you’re dancing, painting, writing songs, poetry, or journaling— is driven by love and the intense feelings it brings. Love can turn any of us into a muse-inspired poet. That’s why I believe that all of us can write inspired songs and poetry. And we should. It’s an expression and acknowledgment of our deepest emotions.

What is a muse?

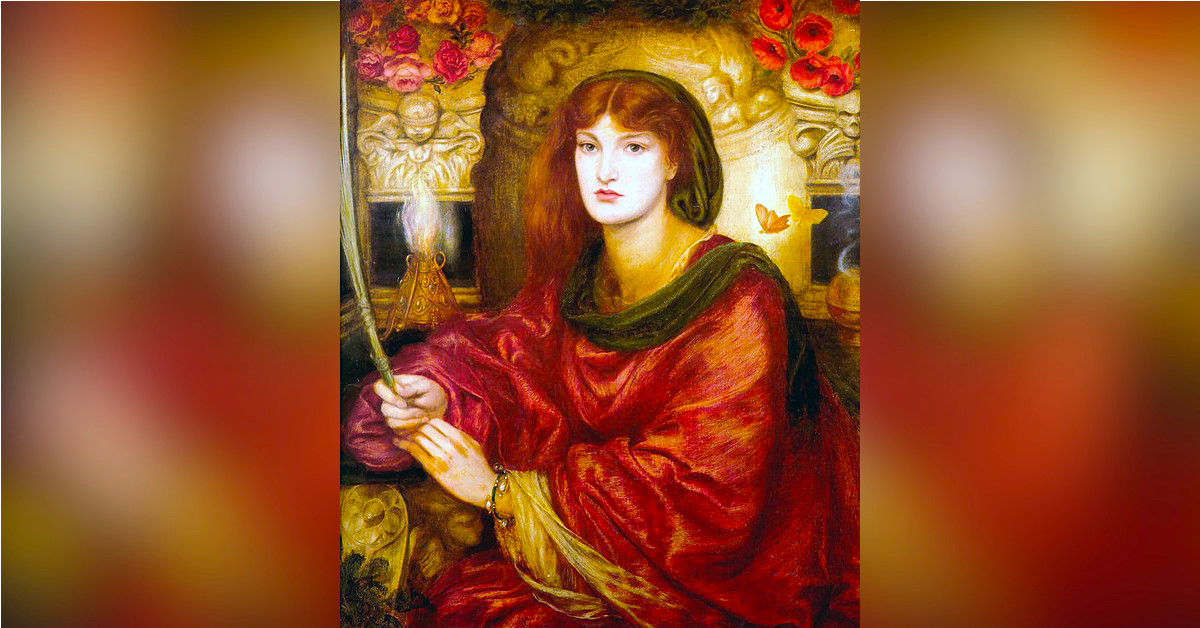

Most people think of the muse as an elegant figure in flowing robes frozen in time on some ancient Grecian urn. Robert Graves, the British poet and novelist, equates the muse with the White Goddess or Triple Goddess of the ancient Celts: she who wields the power of life and death, inspiring awe and fear, love and lust in everyone with eyes to see her. But most people, I think, have seen her without realizing who she was.

In his book The White Goddess, Robert Graves is very specific in his description of the muse: “The muse is a lovely, slender woman with a deathly pale face, lips red as rowan-berries, startlingly blue eyes and long fair hair…” But this portrait is far too limited. Every poet finds his or her own muse – the irresistible figure that draws the artist toward the light of creativity.

The Pre-Raphaelite painters sought out this idealized representation of the muse in real women and painted them again and again. Keats described a fatal encounter with her in his poem “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” The legend of King Arthur celebrates her multiple faces in the figures of Guinevere and Morgan Le Fey.

The experience of the muse is universal; you will find references to her in the poetry and songs of all languages. In India her hair is black, in Africa her skin is dark. The muse is not always female, either. There are poems, paintings, songs, and novels inspired by male muses, too.

The beloved “other”

Perhaps the best way to describe an encounter with the muse is this: somewhere in your past there is a person who comes back to you in dreams. Maybe you barely knew them, perhaps it was only a brief encounter but you have never forgotten the face, the moment, the sudden sense of recognition. The image of this person is surrounded with a special quality of light – a luminous glow that is not present in other memories. There is something magical and transformative about it. This is the face of the muse. The image lives on in your memory, evoking a sense of yearning and the desire to be worthy of this luminous being.

Finding your muse

Many people keep a memory like this but don’t recognize its importance. It usually happens when we are young, between the ages of 18and 25, and we try to dismiss it as “just a crush.” Maybe it makes us feel safer if we can turn it into something trivial and mundane, but the dreamlike image that remains imprinted in the mind and heart is anything but trivial.

Poets, songwriters, painters, artists of all kinds recognize it for what it is: a way in, a doorway into the deep underground of the psyche. It may happen more than once—Picasso had several muses—but for many it is a unique and singularly memorable experience, one that can transform a life.

Why is this meeting so profound? Why does it leave such a lasting and vivid impression? What’s going on here? Well, if you were paying attention at the moment you met your muse, you might have felt something fly out of you and into them – I can’t describe it any other way – it’s that piece of you that Jung calls the anima in a man, animus in a woman.

In an instant, you projected an essential part of your own psyche onto another. What you are seeing when you look at them is the reflection of your own poet-soul. It is frighteningly beautiful, awesome and silent. You want desperately to speak to it but ordinary speech seems inadequate. The only language you can think of to use is art which is the true language of the soul.

This is what makes muses so extraordinarily desirable, the urge to unite with them so irresistible. The muse is a part of your Self, your own soul you are seeing reflected in the Other. That which has been separated yearns to be reunited… but there’s a catch. Like a mirage, the image of the muse dissolves as you approach.

The unobtainable “other”

This is the terrible paradox of the muse: the poet can see, yearn, reach for, worship but never actually possess the muse. Why? Because nothing destroys the elusive beauty of a muse faster than the harsh light of day-to-day familiarity. Artists who actually live with a muse will soon discover he or she has a companion, a friend, a lover, but has lost the radiant source of inspiration. The muse has become a real person and is no longer a shimmering reflection of a soul. Muses are better viewed from a distance.

The theme of the unobtainable muse runs through the work of many poets, painters, and artists of all kinds. Expressing that in a song, a poem, or a painting, is what artists do. Here’s a song of mine written for a young poet entangled with a muse. Feel free to listen on YouTube or Spotify as you read on.

The troubadour’s muse

In the 12th century, the troubadours found a way around this problem; they fell in love with someone who was unobtainable from the start. Their muses were married women of high birth, far beyond the reach of a mere jongleur. Because she was always seen from afar, the lady could embody all the goddess-like qualities the troubadour imagined her to have. They even had a name for it: l’amor de lonh or “distant love.”

The troubadours wrote exquisite songs extolling the virtues of their remote muses, begging for their favors, vowing to die if love went unrequited. But, of course, they knew the lady never could and never would fulfill their desires. She would remain eternally out of reach.

The ghostly muse

Perhaps the most famous unobtainable muse was Dante’s Beatrice. She made her debut as the personification of pure love and keeper of the Gates of Heaven in Dante’s epic poem, The Divine Comedy. What many people don’t realize is that Dante never met Beatrice or, if he did, they exchanged no more than a few words. He claims to have first seen her when they were both nine years old and knew immediately that he was destined to love her always.

Beatrice was married off at eighteen to a man chosen for her by her parents; she probably died at about the age of twenty. But Dante preserved an image of her in his mind long after she was gone, an image that inspired him to create one of the greatest poems ever written. Dante’s idealized Beatrice was a magnificent reflection of his own poet-soul, a shimmering, angelic beacon. (I do sometimes wonder what Dante’s wife might have thought of all this.)

The ancient Celts of Britain, as Robert Graves points out in The White Goddess, seem to have had an especially powerful affinity for this unearthly, dream-like muse. Many haunting celtic ballads describe a lover who appears in the night, surrounded by a halo of light, and departs with the dawn.

A beautiful example is the traditional folk song, “Black Is The Color Of My True Love’s Hair.” Its mournful melody and yearning lyrics describe a lover who is both real and unreal, someone with whom the singer longs to be united but never will be, someone shining with an radiant beauty. I tried to capture some of the power this figure wields —a true folk image of a muse—in my song “Blue Flame.” The melody is based on a song by the troubadour Bernart de Ventadorn, “Quan vei la lauzeta” (“When I see the lark…”), written more than eight centuries ago.

Creating muse-driven art

We reach out and connect with the muse through art. By representing the muse’s presence in painting, writing, dancing, sculpting, or drawing, we can begin to reunite with the piece of us the muse represents.

Journaling is an excellent first step in connecting with the projected psyche. What do you want to or need to tell your muse? What would you like to show your muse about your life? How do your feel about your life? What would make you happy, give you a sense of completion? Talk to your muse in your journal. Draw pictures. Record a melody idea that haunts you. You can use this material as a basis for creating poems, songs, and drawings.

Always keep your journal honest. Express what you really feel. The muse doesn’t demand flowery sentiment and will turn and run at the slightest hint of an untruth. Sometimes you’ll throw caution to the winds. Other times you’ll tiptoe carefully around what you need to say. The muse is only interested in hearing your authentic voice.

For more on finding your authentic voice, read my post Being Authentic.

As you write or draw, notice the luminous quality of the muse you are addressing—the bright, translucent light of the image in your mind. This the key to understanding that you are calling home a piece of yourself. This is the intense beauty and power of your own soul. Keep working and, little by little, you’ll begin to feel the muse beginning to return to you.

Remember that you’re not writing about or imagining a specific individual, someone you may have met or not. They actually have no real connection to your muse. For some unexplained reason, they’re image became attached to a piece of you that you need to reclaim. Keep that in the back of your mind as you work.

The muse survives

“The concept of the muse is part of the Romantic tradition and this is just not a romantic age,” said UCLA professor David Halle in an article in the Los Angeles Times. But the muse will never die as long as there are people who see the best and most beautiful part of themselves reflected in the face of another. Romantic (and unromantic) ages come and go but the muse has been with us since long before the Greeks were painting vases.

Ever since the first human fell madly in love, we’ve been chasing our muses and offering up our best achievements in an effort to entice the elusive dream to come a little closer. “Everything I did, I did for you” is a phrase that surely signifies the presence of a muse.

The muse inspires not just artists, but scientists, philosophers, teachers, anyone who aspires to achieve something that is beyond their reach. And because of our longing for the muse, we become more, better… deeper, wider.

Whatever you do in life, if you have a poet’s soul, embrace your muse. Reach for it, reach beyond yourself, write with the knowledge that the beauty you see is not separate from you but a part of you. The best, most beautiful part. May your songs and stories and paintings and dances flow on.

Robin Frederick

P.S. Here’s one last lesson I learned from my muse. There are things beyond what we can see or understand, things that exist in the heart only. Share with others what you learn from your muse.

Keep following the muse…

Enjoy my Youtube playlist of songs about artists, poets, and muses, including tracks by Don McLean, Nick Drake, Van Morrison, Kenny Chesney, Kate Wolf, The Weepies, and more. Immerse yourself in muse-ness.

Robin Frederick is a professional songwriter, music producer and recording artist. She is a former Director of A&R for Rhino Records , Executive Producer of 60 albums, and the author of seven best-selling books on songwriting, including “Shortcuts to Hit Songwriting” and “Shortcuts to Songwriting for Film & TV.” Request permission to reprint.