Also by Robin Frederick:

Nick Drake: A Place To Be and Nick Drake: An Artist Found.

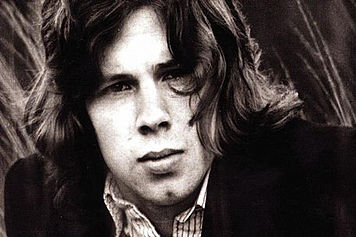

Although Nick Drake has been justly praised as an innovative guitarist, little has been said about the skill and inventiveness he brought to the craft of songwriting. He was, in fact, a world-class songwriter who quietly expanded the boundaries of melody, harmony, and rhythm in pop songwriting. He was not one to draw attention to himself, though, and his songs reflect that fact; everything is seamlessly interwoven and deceptively simple sounding. Beneath the calm surface, however, lies the proof of a singular talent.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I listened to Nick Drake’s albums for many years before I ever noticed what was going on. But when I finally did, it opened the door to new ways of thinking about and writing songs. I have been a professional songwriter all my adult life but there are many things Nick did that I still haven’t mastered. He was only 26 when he died; I can’t even imagine what he would have accomplished had he lived.

First, there were the things he did that were unique to him: offsetting melodic phrases so they didn’t begin or end in the expected place; holding a melody line through a chord change to create ephemeral passing chords; and a preference for unusual or unexpected shifts in rhythm patterns.

Then there were techniques he borrowed from others but used in inventive ways such as unorthodox guitar tunings and cluster chords. He also mastered the use of prosody in which the music underscores and reinforces the lyrics of a song, increasing the emotional impact of both. All of these songwriting techniques and tools were blended together to create the marriage of despair and beauty that characterize his work.

If you are reading this, I assume you are a fan of Nick Drake’s music. Many fans don’t want to analyze Nick’s songs and I certainly don’t blame you. It’s enough just to sit back and listen and let the albums work their magic, as I did for many years. But as Nick’s popularity increases, critics have sometimes found him an easy target, discounting his work as little more than adolescent romanticism. I’d like to see if I can shine a little light on what he really did, especially since, for so many years, it remained hidden.

Prosody in “Fly”

I suppose the best way to demonstrate just how good a songwriter Nick was, is to give a few examples.

In the song Fly, Nick uses the melody to underscore the lyrics in a remarkable way. The verses alternate: the melody is sung first in a high octave, then a lower one. In the verses with the higher melody, the words are those of someone pleading, someone needy and helpless, like a child. Please… give me a second grace. The high voice perfectly reinforces the feeling of childlike fragility and helplessness.

In the second verse, however, the same melody is sung an octave lower. Here the comparable lyric is Now, if it’s time for recompense for what’s done…. Suddenly this is an adult speaking, talking about “recompense” almost like an accountant. The low voice is the voice of experience, weighing the pros and cons and ultimately deciding it’s really too hard to fly.

This is a perfect example of ‘prosody’; the melody underscores and enhances the emotional content of the lyrics. If you’re interested in a little experiment, try switching the lyrics, singing the high verse lyric on the lower octave and vice versa. See how different it feels. The song is not nearly as effective.

Flowing rhythms

Nick Drake also makes extrordinary use of rhythm in many of his songs, often working in unusual time signatures – 5/4 in River Man and many variations of 3/4. (I’ve written about the use of 5/4 and the song River Man in Nick Drake: An Artist Found.) Most of these time signatures are foreign to pop songs which are almost always based on simple 4/4 time. There’s a reason for that: in 4/4 time you always know where you are. Beat 1 gets the most emphasis, Beat 3 somewhat less. Beats 2 and 4 are called the “back beats,” usually played by a snare. Then, Beat 1 again. It’s a solidly constructed square! It’s also what we expect, what we are used to hearing.

Nick took those expectations and turned them back on us. By using time signatures based on three beats per bar instead of four, we sense each bar starting before it should, before we are ready. It’s the dizzy feeling of a spinning waltz or flowing water.

The floating world of “Cello Song”

The sense of being disconnected from solid ground, floating, or lost, is central to Nick’s music and an essential part of his message and persona. He primarily uses rhythm and meter to accomplish it. Here’s an example: In Cello Song, Nick begins the intro by emphasizing the upbeat after Beat 1 – that’s where the guitar riff comes in. But just a few bars later something has changed; now the riff starts on Beat 1 itself.

Then he settles into a new rhythm pattern, giving us the sense that everything will be a little more normal from now on, only to have the cello line start on the highly unusual Beat 3. From here on, the melody shifts between Beat 1 and Beat 3. Just try singing along! It’s almost impossible and yet it’s a very simple melody. By shifting our perception of the strong beat, Nick has created a sense of uncertainty, literally raising the question “Where am I?”

Over and over, Nick finds ways to make Beat 1, that rock-solid fundamental of rock, into an ambivalent question mark. And each time he does it we are left hanging somewhere out in space. Without exception, pop songwriters place their most important words and melody notes on Beat 1. Nick almost always places them on Beat 3… or Beat 2. Anywhere but Beat 1. You can hear this in songs like Which Will, Pink Moon, Hazey Jane I, Fly. Or he will play a two-bar chord phrase and start the melody at the beginning of the second bar which creates the same effect. He does this in the song Place To Be. (I’ve written in more depth about this song in my article Nick Drake: A Place To Be.)

But was it intentional?

People have asked if I think Nick was aware of what he was doing, was it intentional. I honestly don’t know and unfortunately we can’t ask him; we can only look at what he did. John Martyn has told me he thinks it was not intentional, that it was “just the way he (Nick) heard things.”

But it seems to me there was a conscious effort to explore these ideas. Even on very early home demo tapes, Nick was consistently adding measures of 5/4 to a song he was covering (Get Together) and radically altering the rhythms of Bob Dylan’s songs. He was interested in the effect of rhythm right from the beginning and continued to work with it throughout his life.

Perhaps Nick stumbled upon these ideas by accident at first, but they quickly bdrew him in. There are so many variations on the theme, new ways of using the same idea, as if twisting a prism this way and that and observing the colors it throws off. I don’t believe this could have been completely unintentional.

Many new artists are being compared to Nick Drake, but the parallels seem to be mostly a matter of personal style: a dark, introspective romanticism. This is fine as far as it goes, but it isn’t enough to ensure the recognition his work deserves. An artist’s stature grows in direct relation to the number of other artists who build upon what he has done. In only three albums, just 31 songs, Nick pioneered a unique approach to songwriting that is part poetry and part film underscore. It is atmospheric and ambient as opposed to linear and catchy. It is not mainstream; it is mood-stream. There was really nothing like it when he was alive, nor has there been since. Perhaps that’s why it’s taken us so long to catch up to him. It certainly took me long enough.

And now that you know…

So what does a songwriter do with all this once he or she finally gets it? When, at long last, I began to understand the songwriting territory Nick had opened up, I just had to see where it would take me.

Most of the songs on my album WATER FALLS DOWN have been deeply influenced by or are the direct result of what I’ve learned from listening closely to Nick’s music. You can hear melodic phrases that begin on Beat 3 (O Sleeper, O Outsider), melody notes that sustain through cluster chords (Angel, Cover Me), and prosody (California Girl).

I don’t mean to imply that my albums sound like Nick’s. I’m a keyboard and synth player, not a guitarist. I like sequenced drums and world-beat loops; things that didn’t exist when Nick was recording. However, I am using many of the musical tools and techniques he explored over and over in song after song. they’ve opened up doors for me into whole new worlds of melody and rhythm. And I hear his influence in the melodies of some of today’s best singer-songwriters, like Iron & Wine, Alexi Murdoch and Ingrid Michaelson.

There are also two songs on WATER FALLS DOWN that were written about Nick. Although our lives crossed when we both lived in the south of France, it wasn’t until I began listening closely to his music many years later that I felt I began to know him. Like many artists, he was more comfortable revealing himself in his art than he was in life. For songwriters, songs are truly lines in a conversation. When we learn from one another, we keep the conversation alive.

In memory of Nick Drake…

Robin Frederick

©2001 Robin Frederick

Request permission to reprint.

Robin Frederick is a professional songwriter, music producer and recording artist. Nick Drake’s recording of her song Been Smoking Too Long appears on the FAMILY TREE album. She is also a contributor to the album notes in the re-release of the FRUIT TREE box set and FAMILY TREE CD, and the book REMEMBERED FOR A WHILE.

Over her 35 years in the music industry, Robin has written more than 500 songs for television, records, theater, and audio products. She is a former Director of A&R for Rhino Records, Executive Producer of 60 albums, and the author of five books on songwriting, including “Shortcuts to Hit Songwriting” and “Shortcuts to Songwriting for Film & TV.”

Robin’s books are used to teach songwriting at universities and schools at all grade levels. They’re fun to read and filled with practical, real world information. For more information, visit Robin’s Author Page at Amazon.